R Basics Continued

Objectives

In this lesson we will introduce two more data types: factors and data frames. Factors are the data type R uses to store categorical data. Data frames are probably the most commonly used data type in R, and is most similar to Excel spreadsheets. We will learn how to import data into R as a data frame, and in subsequent lessons how to manipulate, modify, summarize, and plot data contained in data frames.

Factors

Factors are how R stores categorical information, like the

continents, among our examples. It is like a character vector that can

only have a finite number of values. To make a factor, we can pass an

atomic vector into the factor() function. In the

background, R recodes the data as integers and stores the results in an

integer vector. It also adds a levels attribute to the

integer vector enumerating the set of labels for displaying the factor

values. The easiest way to see this is with an example:

continents_factor = factor(continents)

continents_factor[1] Asia Africa South America North America

Levels: Africa Asia North America South Americatypeof(continents_factor)[1] "integer"class(continents_factor)[1] "factor"as.integer(continents_factor)[1] 2 1 4 3We observe a few things with this string of commands:

- It looks like the type of

continents_factoris an integer vector. - But there is a class of vectors, called factors. R will often take into account the class of an object to decide how a function will act on it.

- By default the

levelsof a factor are the unique elements of the character vector in alphabetical order.

You can specify an order by explicitly defining the levels as in:

continents_factor = factor(continents, levels = c('South America', 'Asia', 'Africa', 'North America'))

continents_factor[1] Asia Africa South America North America

Levels: South America Asia Africa North Americaas.integer(continents_factor)[1] 2 3 1 4Notice that the integer representation of the vector changed order, because the levels changed order. This will be useful later in the RNA-seq Demystified lessons when we discuss testing for differential expression and the assumptions DESeq2 makes about what factor level is the “reference”.

Data Frames

Data frames group vectors together into a two-dimensional table, where each vector becomes a column of the table. The data types within each column must be the same (they are vectors after all), but the columns can be of different data types. Let’s construct our first data frame using some vectors we have laying around. Here we will include column names from the start:

country_df = data.frame(countries = countries, continents = continents, populations = populations)

country_df countries continents populations

1 Thailand Asia 69950850

2 Lesotho Africa 2108328

3 Suriname South America 575990

4 Canada North America 38436447dim(country_df)[1] 4 3Since data frames are two-dimensional, we have to specify both the row and column to extract specific entries, as in:

# Return the element in the second row, third column

country_df[2, 3][1] 2108328Since the columns of the data frame are named, we can also use those instead:

# Return the element in the Lesotho row of the population column

country_df[2, 'populations'][1] 2108328To access an entire row or column, we specify just the row or column index, as with:

# Access the third row by index

country_df[3, ] countries continents populations

3 Suriname South America 575990And it is the same with columns:

# Access the second column by index

country_df[, 2][1] "Asia" "Africa" "South America" "North America"# By name

country_df[, 'continents'][1] "Asia" "Africa" "South America" "North America"Finally, data frames have another way to access columns using “dollar-sign notation”:

country_df$continents[1] "Asia" "Africa" "South America" "North America"Working with spreadsheets

A substantial amount of data is tabular, that is data arranged in rows and columns - also known as spreadsheets. We could write a whole lesson on how to work with spreadsheets effectively (actually, Data Carpentry has). For our purposes, we want to remind you of a few principles before we work with our first set of example data:

1. Keep raw data separate from analyzed data

This is principle number one because if you can’t tell which files are the original raw data, you risk making some serious mistakes (e.g. drawing conclusion from data which have been manipulated in some unknown way).

2. Keep spreadsheet data Tidy

The simplest principle of Tidy data is that we have one row in our spreadsheet for each observation or sample, and one column for every variable that we measure or report on. As simple as this sounds, it’s very easily violated. Most data scientists agree that significant amounts of their time is spent tidying data for analysis. Read more about data organization in this lesson and in this paper.

3. Trust but verify

Finally, while you don’t need to be paranoid about data, you should have a plan for how you will prepare it for analysis. You probably already have a lot of intuition, expectations, assumptions about your data - the range of values you expect, how many values should have been recorded, etc. Of course, as the data get larger our human ability to keep track will start to fail (and yes, it can fail for small data sets too). R will help you to examine your data so that you can have greater confidence in your analysis, and its reproducibility.

Tip: Changes in R don’t overwrite the original file

When you work with data in R, you are not changing the original file you loaded that data from. This is different than (for example) working with a spreadsheet program where changing the value of the cell leaves you one “save”-click away from overwriting the original file. You have to purposely use a writing function (e.g.

write.csv()) to save data loaded into R. In that case, be sure to save the manipulated data into a new file. More on this later in the lesson.

Importing tabular data into R

There are several ways to import data into R. For our purpose here,

we will focus on using the tools every R installation comes with (so

called “base” R) to import a comma-delimited file containing the results

of our variant calling workflow. We will need to load the sheet using a

function called read.csv().

Exercise: Review the arguments of the

read.csv()functionBefore using the

read.csv()function, use R’s help feature to answer the following questions.Hint: Entering ‘?’ before the function name and then running that line will bring up the help documentation. Also, when reading this particular help be careful to pay attention to the ‘read.csv’ expression under the ‘Usage’ heading. Other answers will be in the ‘Arguments’ heading.

- What is the default parameter for ‘header’ in the

read.csv()function?- What argument would you have to change to read a file that was delimited by semicolons (;) rather than commas?

- What argument would you have to change to read file in which numbers used commas for decimal separation (i.e. 1,00)?

- What argument would you have to change to read in only the first 10,000 rows of a very large file?

Solution

- The

read.csv()function has the argument ‘header’ set to TRUE by default, this means the function always assumes the first row is header information, (i.e. column names) - The

read.csv()function has the argument ‘sep’ set to “,”. This means the function assumes commas are used as delimiters, as you would expect. Changing this parameter (e.g.sep=";") would now interpret semicolons as delimiters. - Although it is not listed in the

read.csv()usage,read.csv()is a “version” of the functionread.table()and accepts all its arguments. If you setdec=","you could change the decimal operator. We’d probably assume the delimiter is some other character. - You can set

nrowto a numeric value (e.g.nrow=10000) to choose how many rows of a file you read in. This may be useful for very large files where not all the data is needed to test some data cleaning steps you are applying.

Now, let’s read in the file data/gapminder_data.csv and

call this data gapminder. The first argument to pass to our

read.csv() function is the file path for our data. The file

path must be in quotes and now is a good time to remember to use tab

autocompletion. If you use tab autocompletion you avoid typos

and errors in file paths. Use it!

## read in a CSV file and save it as 'gapminder'

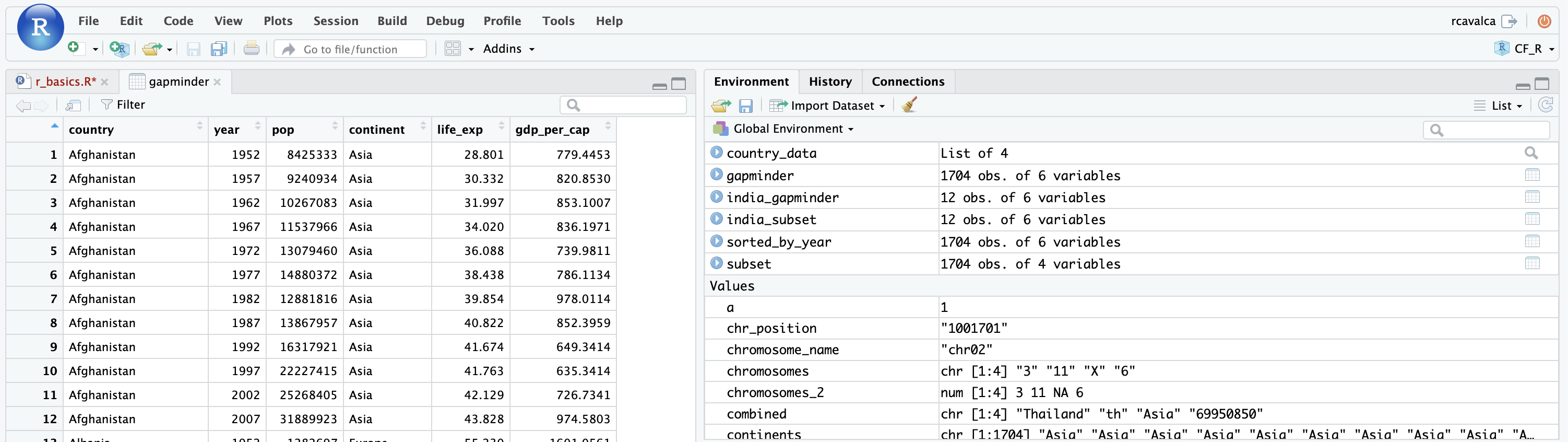

gapminder <- read.csv("data/gapminder_data.csv")One of the first things you should notice is that in the Environment

window, you have the gapminder object, listed as 1704 obs.

(observations/rows) of 6 variables (columns). Double-clicking on the

name of the object will open a view of the data in a new tab.

Summarizing, subsetting, and structure of a data frame

A data frame is the standard way in R to store tabular data. Remember, a data frame is a collection of vectors, all of which have the same length. Using only two functions, we can learn a lot about our data frame including some summary statistics as well as well as the “structure” of the data frame. Let’s examine what each of these functions can tell us:

## get summary statistics on a data frame

summary(gapminder) country year pop continent

Length:1704 Min. :1952 Min. :6.001e+04 Length:1704

Class :character 1st Qu.:1966 1st Qu.:2.794e+06 Class :character

Mode :character Median :1980 Median :7.024e+06 Mode :character

Mean :1980 Mean :2.960e+07

3rd Qu.:1993 3rd Qu.:1.959e+07

Max. :2007 Max. :1.319e+09

lifeExp gdpPercap

Min. :23.60 Min. : 241.2

1st Qu.:48.20 1st Qu.: 1202.1

Median :60.71 Median : 3531.8

Mean :59.47 Mean : 7215.3

3rd Qu.:70.85 3rd Qu.: 9325.5

Max. :82.60 Max. :113523.1 Our data frame has 6 variables, so we get 6 fields that summarize the

data. The year, pop, lifeExp and

gdpPercap variables are numerical data and so you get

summary statistics on the min and max values for these columns, as well

as mean, median, and interquartile ranges. The other variables,

country and continent, are treated as

characters data (more on this in a bit).

Now let’s use the str() (structure) function to look a

little more closely at how data frames work:

## get the structure of a data frame

str(gapminder)'data.frame': 1704 obs. of 6 variables:

$ country : chr "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" ...

$ year : int 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 ...

$ pop : num 8425333 9240934 10267083 11537966 13079460 ...

$ continent: chr "Asia" "Asia" "Asia" "Asia" ...

$ lifeExp : num 28.8 30.3 32 34 36.1 ...

$ gdpPercap: num 779 821 853 836 740 ...Some things to notice.

- the object type

data.frameis displayed in the first row along with its dimensions, in this case 1704 observations (rows) and 6 variables (columns) - Each variable (column) has a name (e.g.

country). This is followed by the object mode (e.g. chr, int, etc.). Notice that before each variable name there is a$- which is a hint as to how one can access these columns, as we saw when we first introduced data frames.

We saw how to subset a data frame in the previous section, but in all those examples we printed values to the screen. You can create a new data frame object by assigning them to a new object name:

# create a new data frame containing only observations from India

india_subset <- gapminder[gapminder$country == "India",]

# check the dimension of the data frame

dim(india_subset)[1] 12 6# get a summary of the data frame

summary(india_subset) country year pop continent

Length:12 Min. :1952 Min. :3.720e+08 Length:12

Class :character 1st Qu.:1966 1st Qu.:4.930e+08 Class :character

Mode :character Median :1980 Median :6.710e+08 Mode :character

Mean :1980 Mean :7.011e+08

3rd Qu.:1993 3rd Qu.:8.938e+08

Max. :2007 Max. :1.110e+09

lifeExp gdpPercap

Min. :37.37 Min. : 546.6

1st Qu.:46.30 1st Qu.: 690.2

Median :55.40 Median : 834.5

Mean :53.17 Mean :1057.3

3rd Qu.:60.61 3rd Qu.:1238.0

Max. :64.70 Max. :2452.2 Coercing data

When we looked at summary(gapminder) and

str(gapminder), we noticed the type for continent was

character, but perhaps a factor is more

appropriate here because there are only a small number of possible

values. We can “coerce” the continent column of

gapminder to be a factor using the factor()

function.

# Coerce the continent column to a factor

gapminder$continent <- factor(gapminder$continent)And let’s see how the result of summary() and

str() change in response:

summary(gapminder) country year pop continent

Length:1704 Min. :1952 Min. :6.001e+04 Africa :624

Class :character 1st Qu.:1966 1st Qu.:2.794e+06 Americas:300

Mode :character Median :1980 Median :7.024e+06 Asia :396

Mean :1980 Mean :2.960e+07 Europe :360

3rd Qu.:1993 3rd Qu.:1.959e+07 Oceania : 24

Max. :2007 Max. :1.319e+09

lifeExp gdpPercap

Min. :23.60 Min. : 241.2

1st Qu.:48.20 1st Qu.: 1202.1

Median :60.71 Median : 3531.8

Mean :59.47 Mean : 7215.3

3rd Qu.:70.85 3rd Qu.: 9325.5

Max. :82.60 Max. :113523.1 str(gapminder)'data.frame': 1704 obs. of 6 variables:

$ country : chr "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" "Afghanistan" ...

$ year : int 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 ...

$ pop : num 8425333 9240934 10267083 11537966 13079460 ...

$ continent: Factor w/ 5 levels "Africa","Americas",..: 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 ...

$ lifeExp : num 28.8 30.3 32 34 36.1 ...

$ gdpPercap: num 779 821 853 836 740 ...Notice that we got some additionally useful information from

summary() from the coercion. Namely, we get the number of

entries in gapminder that are on each continent.

Tip: Treating objects as categories without changing their mode

You don’t have to make an object a factor to get the benefits of treating an object as a factor. See what happens when you use the

as.factor()function ongapminder$continent. To generate a tally, you can sometimes also use thetable()function; though sometimes you may need to combine both (i.e.table(as.factor(object)))

Note: StringsAsFactors

There are explicit forms of coercion, as in our factor example above. But there are also implicit coercions. The most famous example of this in R is the

stringsAsFactorsparameter ofread.table(). Prior to R 4.0, when importing a data frame thestringsAsFactorsargument wasTRUEby default, which caused all character columns to be factors by default. This wasn’t a good default behavior, and the default is nowFALSE.

Saving your data frame to a file

We can save data to a file. We will save our

india_subset object to a .csv file using the

write.csv() function:

write.csv(india_subset, file = "results/india_subset.csv")The write.csv() function has some additional arguments

listed in the help, but at a minimum you need to tell it what data frame

to write to file, and give a path to a file name in quotes (if you only

provide a file name, the file will be written in the current working

directory).

Data tips

At the beginning of the lesson we suggested three things when dealing with data in R:

- Keep raw data separate from analyzed data

- Keep spreadsheet data Tidy

- Trust but verify

As we all know, data can be messy–errors can be made when entering

it–and at some point those errors need to be corrected. To elaborate on

“Trust but verify,” consider the fact that in the gapminder

data set we had many countries over many continents, and any misspelling

could cause problems when summarizing the data. For instance, “North

America” could accidentally be entered as “NorthAmerica” or “North

america”. When reading in data, it’s a good idea to check that there

aren’t any odd things happening like this.

For character / categorical data, simply looking at the unique elements of a column can help detect errors quickly:

unique(gapminder$continent)[1] Asia Europe Africa Americas Oceania

Levels: Africa Americas Asia Europe OceaniaIn this case, we don’t see any obvious misspellings that could cause problems. For numeric data, looking at a summary of the column to see the min/max values, as well as the mean/median, can help determine if any obvious errors are present.

summary(gapminder$pop) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

6.001e+04 2.794e+06 7.024e+06 2.960e+07 1.959e+07 1.319e+09 In this case, we don’t notice any values that might be out of the ordinary. For example, we know that there are countries with over a billion people, so seeing a maximum of 1,319,000,000 is not strange. At the same time, we know there are very small countries, so seeing a minimum of 60,000 seems reasonable too. What would be unreasonable would be a negative population, for example.